Lindsey Ross

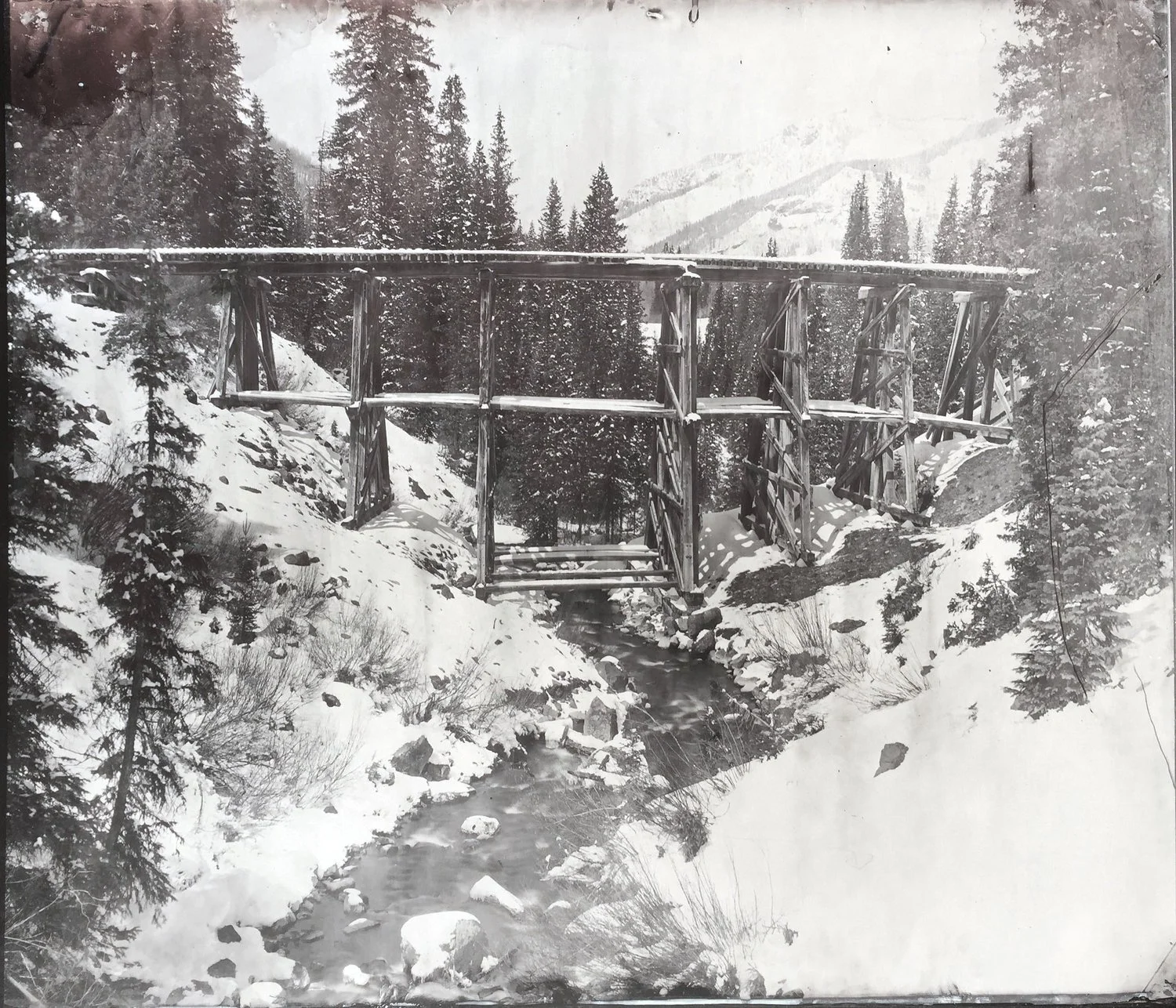

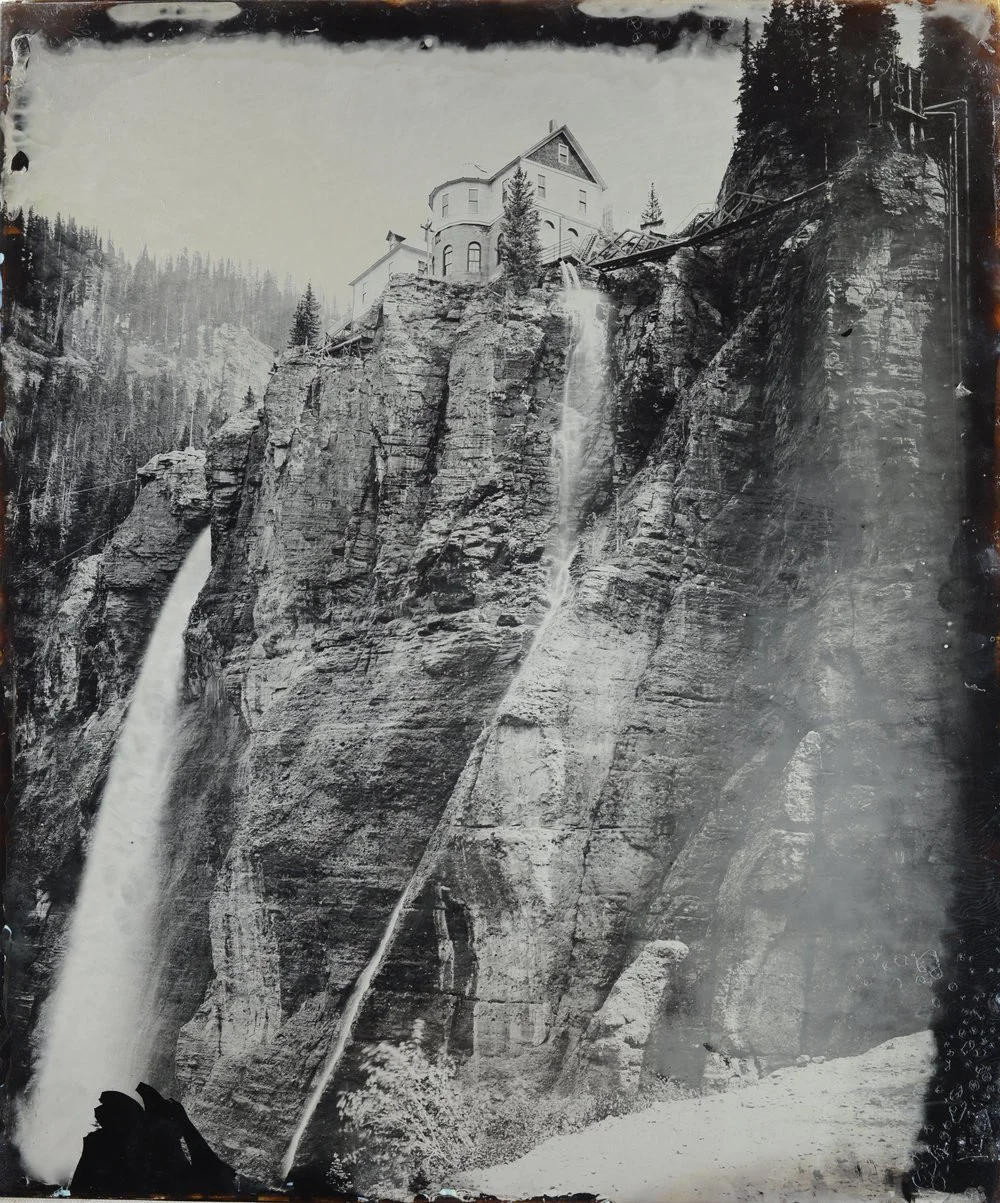

Lindsey Ross, from the series ‘ Ingress, Egress, Regress’

The Struggle Defines the Aesthetic: Lindsey Ross’s Antiquated Masterpieces

This past spring, Lindsey Ross took the Amtrak Surfliner down the coast of southern California, to install a 20-by-24-inch glass plate photograph at an engineering firm in San Diego. The image was of a power station perched above Bridal Veil Falls, near Telluride, CO, and her commission was a partial trade for a mid-2000s Ford F-150 pickup. Nothing fancy, but it was in good condition and had an extended bed. The stickered serial number on the side indicated it had belonged to a fleet of other white work trucks. It was her third that year. She’d worn out the other two.

With her petite frame and easy smile, it might be difficult to picture Ross—in thick canvas coveralls and steel-toed Redwing boots—maneuvering her 200-pound camera in the snowy Colorado wilderness or the stark California desert, let alone regularly driving trucks to early deaths. But this was her third in a year, a testament to the rugged terrain she covers and her hard, unrelenting work ethic.

Ross’s particular artwork requires gear, and lots of it. While she will opt for rolls of expired film during ski trips, her established medium is wet-plate collodion, a 19th-century photographic process recorded on a substrate of glass or metal. It’s incredibly labor-intensive, and results in tangible, one-of-a-kind pieces, meditations on places and people who seem to straddle modern limits of timelessness.

Among her most recent projects are snow-covered mining ruins in Telluride, CO, and lit-up yucca plants in Joshua Tree, CA at night. But, over the years, her subject matter has included a conceptual war-torn America, transcendent root vegetables, and Sweetgrass Production’s 2013 film VALHALLA. One constant, however, has been portraiture. This is in part out of economic necessity, but primarily to record the characters she encounters: psychedelic musicians, conceptual artists, and dedicated skiers.

Ross grew up in the rust belt outside of Columbus, OH, watching people come back to their hometown to build safe, stable lives in the suburbs. This is not typically the artist's life, nor is it that of the ambitious skier or outdoorswoman, so she soon left the flat suburbs of Columbus to explore the American West. She eventually landed in Jackson Hole, WY, where she worked on a ranch, learned to backcountry ski, and began taking photographs. Jackson became her second home, one she documented with a camera from her father. She wasn’t making a living from it, but photography was becoming an important part of her life.

Her career launched in earnest when she pursued an MFA in photography at Brooks Institute in Santa Barbara, CA. There she became interested in outdated ways of capturing images, specifically wet-plate collodion. This antiquated method of photography was predominantly used between 1850-1900, in which sheets of glass or metal are coated in a combination of light-sensitive chemicals. These plates are then set into the back of a camera (in Ross’ case, one she could literally crawl inside), and exposed to light by taking the lens cap off for anywhere from a few seconds to a few minutes. Once the exposure is finished, the plates are developed on-site.

It is a highly physical process, made even more so when done on the side of a mountain, or following a skier into the backcountry for fresh tracks. For portraits in her studio, Ross requires a few hours of set up, mixing chemicals, setting lights, and cutting the glass or metal plates. But when she shoots on location in the mountains, it requires transporting the whole studio, and often hours of work just finding an access point.

There is a lot of life in this process, with no auto-correct or smoothing out of any blemish to some artificial perfection. Time is compressed into one frame, the meeting of a modern subject with a century-old medium. This adds a certain freedom and carefree quality to Ross' work, allowing the expired chemicals or the extreme temperatures to influence the details revealed or marred in the final fixing of light. It’s a freedom attained only by giving up control.

This is an intoxicating approach for Ross, and it must be to make a living at photography the way she does. While she’s currently based in Santa Barbara, she’s almost always on the road, pursuing commercial and personal projects that can last from days to months. This year, she’s journeyed to Telluride, Big Sur, Berlin and Jackson Hole, as she completed commissions, attended art festivals, and began her new series of work: illuminating the desert flora of southern California’s Transverse Mountain Ranges at night.

Last year, Ross’s mine project resulted in her rattling down dark, two-track switchbacks in Cerro Gordo, CA, after the brakes went out in her truck at 7,000 feet. This ended in a crash that totaled the vehicle but thankfully left her intact. Only one of her fragile plates broke, split diagonally in two, which would later give the piece its title, “Made at Tomboy 11,500, Broken in Cerro Gordo 7,500” (2016). These are hard-earned photographs, images that evoke as much as they portray. This is not a life of leisure, and that’s the way Ross likes it: the struggle defines the aesthetic.